Folkestone Free Library: Beginnings

Professor Carolyn Oulton

School of Humanities at Canterbury Christ Church University

Books have always had the power to cause trouble. Ironically the Folkestone Free Library catalogue for 1884 includes Mary Braddon’s Taken at the Flood among other watery volumes. Judging by word frequency in historic newspapers you might think that Victorian libraries were constantly being flooded. In a sense they were. With ‘cheap fiction’, books by women, novels you especially didn’t want your daughters to read.

In the late nineteenth century what came to be known as the Great Fiction Debate hinged on two questions: what does reading do to people and who picks up the tab?

The Public Library Act of 1850 had allowed for the provision of libraries to be paid for out of the rates, but few councils took up the offer before the 1880s. Apathy may be attributable partly to concerns that ratepayers would foot the bill for working class ‘self-culture’. For some readers the thought of handling a book without knowing whose hands had been on it first… (Happy Birthday and fingertip to palm rub, anyone)?

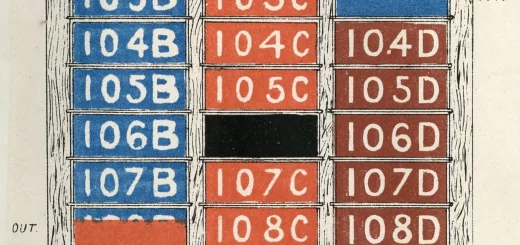

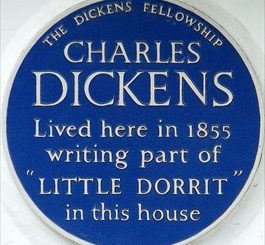

Folkestone was actually an early adopter of the Act, opening a Free Library on the Bayle in 1879. Borrowing was allowed from 1881, to the dismay of Councillor Robinson, who urged that ‘The books would soon be destroyed’. But tourists were drawn in from the start, although as non-ratepayers they were prohibited until at least the 1890s from taking volumes out of the reading room.

The first catalogues included blank pages for donations, suggesting a creative response to budgetary constraints. The library committee decided which books could be admitted and made available to readers. But there were constant complaints in the press about the dangers of reading too much fiction, and libraries nationwide came under pressure not to order in too much of it. In Folkestone one zealous clergyman argued that fiction should not be purchased with ratepayers’ money. For anyone who felt unable to wean themselves off this habit, he proposed that they confine themselves to an exclusive diet of Walter Scott and George Eliot.

Fortunately librarian George Hills was an amenable character; the early catalogues note both donation and purchase of books by controversial sensation authors such as Braddon and Wilkie Collins (both of whom had spent holidays in Kent). It was Hills who oversaw the move to Grace Hill in 1888. On his death two years later he was succeeded by his son Stuart, who seems to have been equally affable. One local journalist commented in 1893:

at the present moment I am reading a volume Mr Hills recommended, and with such keen enjoyment that it has to be taken from me by main force or I should get no meals.

Some of us may remember being told as children, ‘Shh, we’re in a library!’ Those days have long gone, but we all know the influence of the local librarian on the experience of choosing a book. In the days before open access shelving librarians had still more power either to exclude the ‘undesirable’ or to make everyone feel welcome.

With what feels like uncanny prescience the same journal that thanked Hills for his stewardship commented in 1894, ‘those who pay the rates have a perfect right to use the Reading Room.’